Toxic beauty (II)

The second post about historical toxic cosmetics: here I talk about cinnabar and clay (yes, clay can be toxic when you use it the way it was used in 18th century Spain).

Before the holidays, I posted about two historical beauty practices that were highly toxic. In fact, many of the beauty practices from the past, and from today, aren´t healthy from us. In some cases, we are not aware of it, because there hasn´t been a study yet about the repercussions of this or that ingredient. In others, the practice itself is uncomfortable, painful or dangerous, we know, and we still decide to do it. From the perspective of human evolution, this is sometimes a puzzle to think about.

There are two main forces that move evolution forward: one is survival, and the other one is mating. Our desire to be beautiful, from a biological point of view, is connected to the fact that we want to be chosen for mating. I don´t mean everyone wants to have children, but most people want to have sex, a partner or companionship, and we mainly want to be attractive for that reason.

So, if we are willing to risk ourselves to look more attractive, that means the push to mate is stronger that the push to survive (stay alive and healthy), probably because once you´ve had children, you have “fulfilled your purpose” (again, from an evolutive perspective). Therefore, for a species, attracting a mate is more important than survival. You have to survive enough to have offspring, but after that, you are not as relevant for the survival of the species.

I am fascinated about this idea, and about the way we have used certain materials and substances to be beautiful. Today, I talk about cinnabar and clay.

Toxic red: cinnabar

Cinnabar is a red mineral used as a pigment since prehistory. It is a fiery red, closer to orange than most red pigments, especially when it is very finely ground. Cinnabar is naturally found in mercury deposits in the form of mercury sulfide, and it´s not as common as the other historical red pigment— ochre, iron oxide. It has another disadvantage compared to ochre: it is very toxic, especially if you breath mercury´s vapors.

Spain has the biggest mercury mine in the world, the mine of Almaden. The Romans exploited the mine to make vermilion, the red pigment prepared from cinnabar. They knew exploiting the mine was lethal, and only employed prisoners to extract the mineral. While working, the prisoners breathed the mercury´s vapors and got sick. The life expectancy as a miner was a few short years: working in Almaden was a death sentence, and everyone knew it. It is usually said that, in Rome, the worst crimes were punished two ways: you were sentenced to work as a rower in the army´s galleys, or you were sent to Almaden. Either way, you would die rather sooner than later, and it wasn´t a pleasant death.

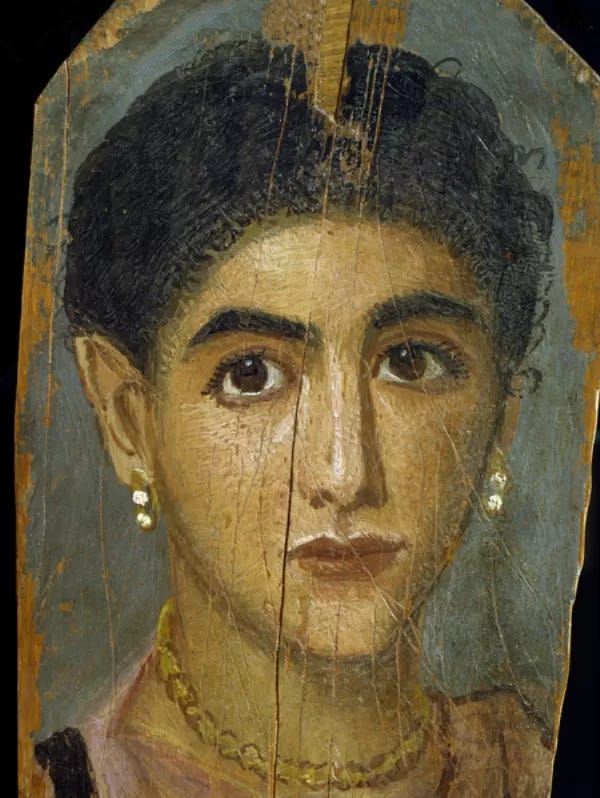

The Romans knew that working to extract cinnabar was incredibly toxic, but then they turned the mineral into makeup. The cinnabar from Almaden (the name means “the mine” in Arabic) was sent to Rome, where it was turned into a fine red pigment. The patricians, the upper class of Roman citizens, were the only ones who could afford to buy this pigment and use it as a cosmetic for lips and cheeks— a classic rouge.

Some symptoms of mercury poisoning are: discoloration of cheeks and fingers, tremors, tachycardia, memory loss, insomnia, nervous system damage, losing your hair, teeth, and nails, and chronic fatigue. It is interesting to notice that most symptoms altered physical appearance for the worse, when it was used for beautification in the first place. I am not sure if they thought that extracting cinnabar was dangerous, but it was then safe to use as a cosmetic, or if they suspected that it wasn´t healthy to coat your lips with vermilion, but they risked it anyway. I am inclined to think the latter.

In India, vermilion is also used as a cosmetic by married women. It´s called sindoor, and it´s a line of red pigment starting on the forehead and covering the hair´s parting. It´s applied for the first time by the husband on their wedding day. Another use of sindoor that it´s more widely known in the West is marking a red dot on the forehead, to the same effect. Women will wear sindoor everyday while they are married, and only stop wearing the red powder if their husbands pass away, to indicate their widowhood. Historically, sindoor was made of turmeric powder and lime, natural plants that are not toxic, but nowadays sindoor often contains vermilion, or even red lead, equally poisonous.

Toxic diet: eating clay

Yes, you read it right: eating clay was apparently a practice in 17th and 18th century Spain, and it was for beauty reasons. I had heard of the practice of eating clay for medicinal reasons. It is said that eating red clay (ochre) can help with stomachaches, and it´s a traditional practice in several places (although I couldn´t say if it really alleviates stomach pain). However, eating clay in the 17th century Spanish court had a different purpose, and it caused several health problems.

Let´s look at one of the most famous paintings in Western art history: Las Meninas (1656) by Diego Velázquez. In this extraordinary portrait of the Spanish royal family, the woman on the left is giving the princess, Infanta Margarita, a reddish clay pot. This pot is called a búcaro, a type of clay pitcher very popular at the time. It wasn´t only a recipient for water, but women also ate it in small bites.

Búcaros were made with a particular kind of clay from Mexico (and sometimes Portugal), and they were modeled in a very thin and delicate ceramic. These pots travelled from America to Spain, and some búcaros arrived broken after the long trip through the Atlantic Ocean. It is possible that these broken pieces were the ones eaten by the noble women. However, in the painting, one interpretation is that that the lady in waiting is giving the unbroken búcaro to the princess to eat it. Maybe it happened both ways: they ate the broken pieces instead of throwing them away, and, in some cases, they bit whole búcaros as well.

Why did they eat clay? one of the effects of eating búcaros was liver damage and anemia, which made women look very pale and sickly, something fashionable at the time. They literally made themselves ill to be beautiful (beautiful as per their society standards). Another symptom was intestinal obstruction, and it caused a swollen belly, stomachaches and constipation— the opposite of the traditional remedy I mentioned before.

Eating clay was also believed to reduce or stop menstruation, and women were recommended to use it as a contraceptive. Búcaros were a multi-purpose item: it could carry water or perfume, it would whiten your complexion, and it could help you enjoy sex without the worry of having a child. There is even a word in Spanish for the act of eating búcaros: bucarofagia, which let us know that this was a known deed at the Spanish court— but probably seemed barbaric outside of it.

It is worth mentioning that they didn´t eat just any clay or any clay pot, but the fashionable thing to do was munching búcaros. I imagine part of the reason was that búcaros came from afar and were a luxury item, made with an exotic soil from the Americas. Along with the months of travelling to arrive to Madrid, this meant only the nobles could afford this imported craftmanship. The more unique and expensive a material is, the more appreciated and ritualized its use. Eating búcaros was exclusive, and a bit pointless: they could have eaten any other clay. But eating something expensive and difficult to obtain, instead of using it for its original purpose, was the quintessential show of power.