Lately, I have been trying to learn about color symbolism in Asia, and expand my knowledge of pigments and dyes in other cultures. I am particularly interested in India, because their pigment tradition is tremendously rich.

With this goal in mind, I´ve been looking for sources of information, and I recently read a paper about the pigments used in a traditional art studio in Jaipur1, India. I read it with huge interest, and one thing stood out over the rest—South Asia has a wonderful palette of yellow pigments that have no equal in the world.

Yellow is not a color that has received much attention in the West. Firstly, because it is a color with a generally negative symbolism2—it can mean betrayal, lying, jealousy, disease, madness, or the Other—so it hasn´t received the same amount of research than red or blue have.

And second, because the availability of yellow pigments was limited: ochre, plus lead and tin yellow were the typically available sources for yellow paint until the 19th century. While weld, Reseda luteola, was the commonly used plant to make yellow dye.

South Asia had no such limitations: yellow is viewed in a religious positive light, and the sources of colorants available were diverse.

After reading about the Jaipuri workshop, I have to say I was a bit jealous. Not only does India have a rich pigment tradition (and wonderful colorants that are hard to come by in other places), but they have kept this tradition alive. I was amazed that this artist still used mostly historical pigments, some of them practically impossible to find outside of India.

I was inspired to do a deep dive into some of the yellow pigments used in South Asia, so get ready for a tale of alchemists, spices, poison, mangoes and cows (yes, cows!).

Indian yellow

Our first stop is one of the most mysterious pigments in the history of colors. It arrived in Europe in the form of balls of a bright yellow pigment, but no one knew exactly what it was.

In 1883, two men showed interest in finding out the precise source of this pigment. One of them was Professor Graebe, a German chemist who was curious to analyze the specific chemical composition of Indian yellow. He wrote to Sir Joseph Hooker, a botanist who was the director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew asking for information and a small sample.

Hooker then made a formal request to the Government of India (under British ruling at the time) to explore the origins of Indian yellow and send back a report. The fortunate worker to receive the task was Trailokya Nath Mukharji, an employee of India's Department of Revenue and Agriculture.

Mukahrji travelled to the Bihar region until he found a small community of milkmen who were considered the only people who manufactured piuri— one of the names for Indian yellow (all historical pigments have many names, which makes research difficult sometimes).

He observed and described the process to make piuri like this: they had a herd of cows that they mostly fed mango leaves and water. This diet made for a particularly yellow urine that the milkmen collected on clay pots, and then left on the fire so the water evaporated, and the pigment remained at the bottom. The substance was filtered, made into balls, and then dried on charcoal and the sun. After that, it was ready to sell in markets all over India, and overseas.

The rumor that Indian yellow came from some ruminant´s urine circulated even in the 19th century—the smell of the yellow balls was foul. Yet it wasn´t believed because it sounded too extravagant to be true.

I knew this story from Victoria Finlay´s book, Color: a natural history of the palette, but she didn´t give it much credit either. In the book, she actually travels to the town of Mirzapur and tries herself to unearth the history of these cows eating mango leaves, but she can´t find any proof.

However, in preparing for this post, I read a recent scientific study3 where a group of researchers had recovered the original samples sent from India—I am amazed that they were still there—and proceeded to analyze the pigments with several methods. And voilá: the results proved that Indian yellow was, in fact, what Mukharji had reported.

I suspect that one of the reasons why the origin of Indian yellow was doubted (besides being a bit bizarre) is because European scientists of the 19th century would hesitate to believe people they considered to be “superstitious” (meaning not white).

Mukharji, however, had made an excellent job: he made a full report, and sent some of the materials used to make Indian yellow (gauze, clay pots), some mango leaves and several samples of the pigment to the Royal Botanical Gardens, Kew.

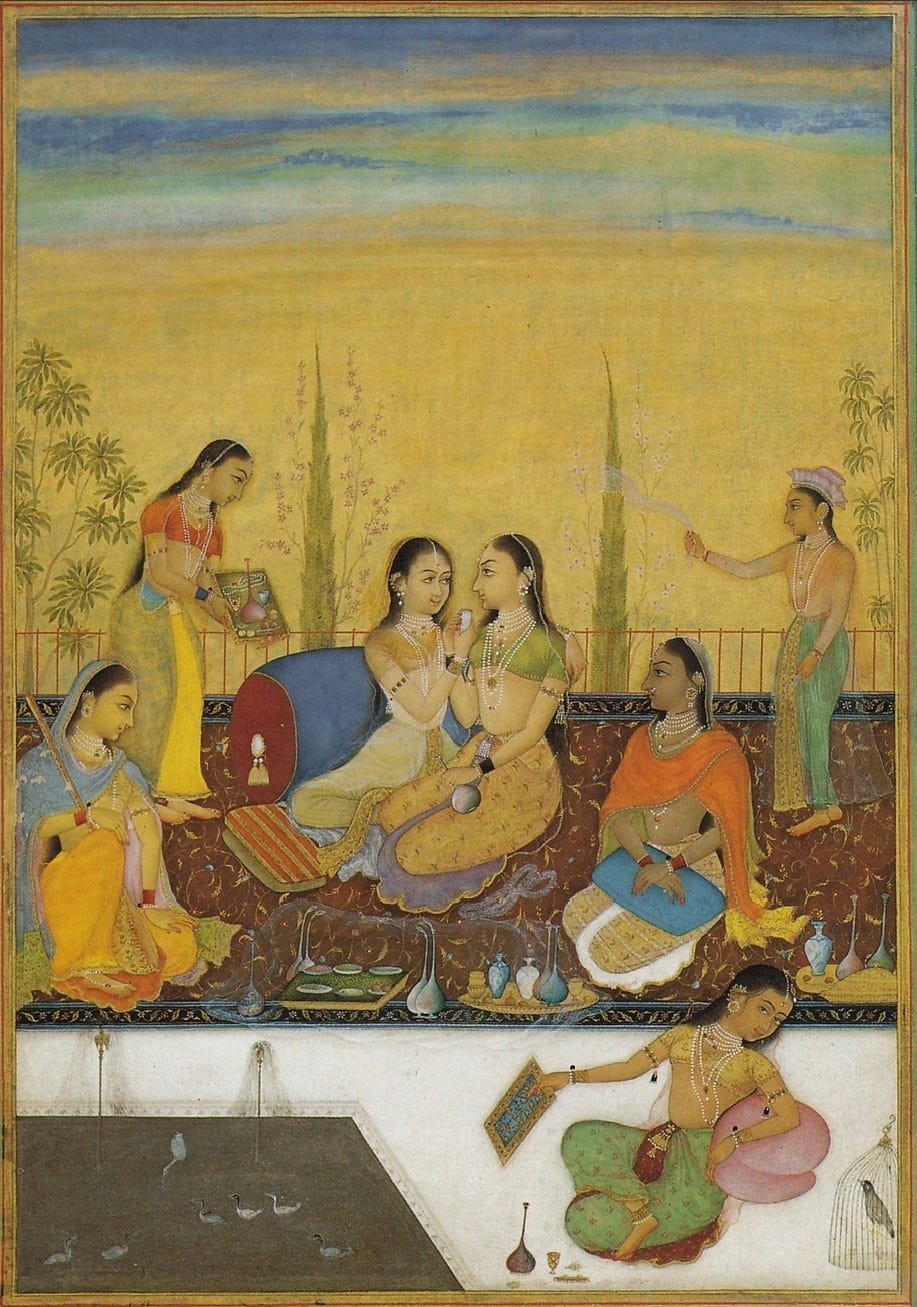

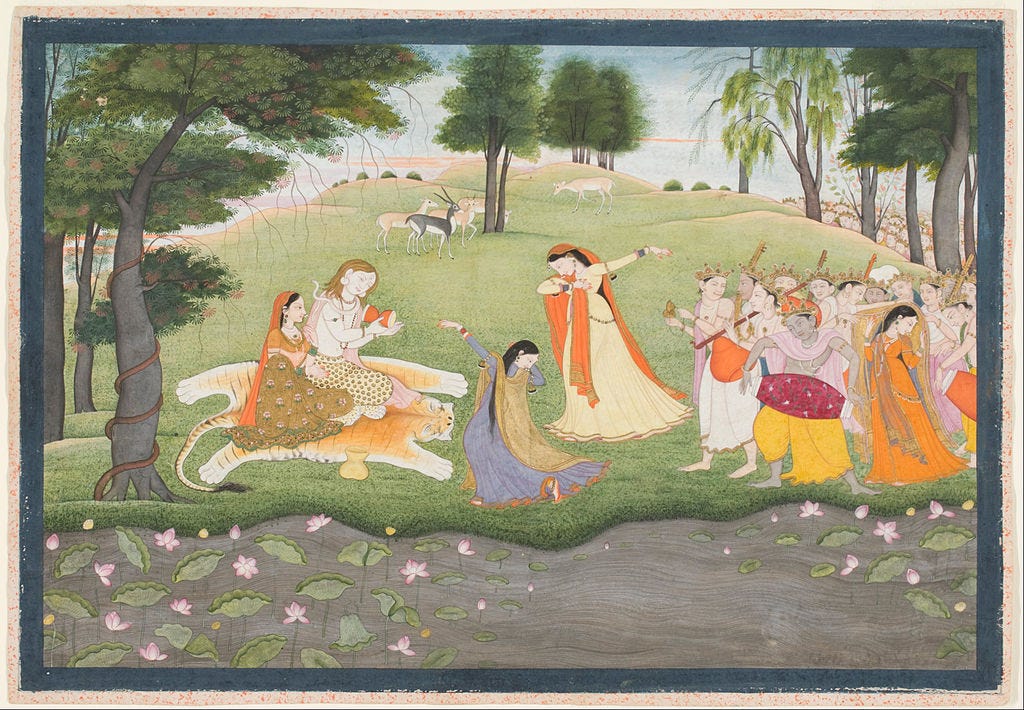

From the 16th to the 20th century Indian yellow was used all over South Asia. It made a beautiful, transparent yellow that could be used in frescoes, watercolors and oil painting, and can be found in many traditional miniature paintings, especially during the Mughal period (1526-1857). In Europe, it was popular during the 19th century, probably because more of the pigment travelled to the West during the peak of the British Empire.

The use of this pigment came to an end at the beginning of the 20th century. Only eating mango leaves, and being forced to urinate all the time, wasn´t very healthy for the cows. They were either malnourished or in pain (Mukharji wrote they looked awful), and cows are venerated in India. The production of piuri was allegedly forbidden in 1908 because of animal cruelty, and organic Indian yellow disappeared shortly after.

Gamboge

Gamboge is another fascinating organic pigment from South Asia. It comes from the latex of the Garcinia tree, indigenous to Cambodia. To tap the milky substance, the trees had to be at least 10 years old. It was necessary to make incisions in the tree trunk, and when the latex came out, it was collected inside hollow bamboo canes. Then the canes were rotated over a fire to extract the substance´s humidity. Once the latex was hardened enough, the bamboo canes were broken to get the gamboge.

The typical presentation of gamboge was brown rods (after the shape of the bamboo) that are composed of approximately 20% water soluble-gum, and 80% insoluble resin. The pigment is in the resin.

As with most natural colorants, the look of the source material is not the actual color of the pigment. When ground into powder, it transforms into a deep golden, and when mixed with water, the gum dissolves, and the resin particles come alive as a bright yellow. The carbohydrate gum acts as a natural binder, which makes it into an ideal watercolor—its primary use throughout history.

The use of gamboge has been traced back to the 8th century in East Asia and Japan. Besides being a watercolor, it can be used in glazes, varnishes and to dye fabric.

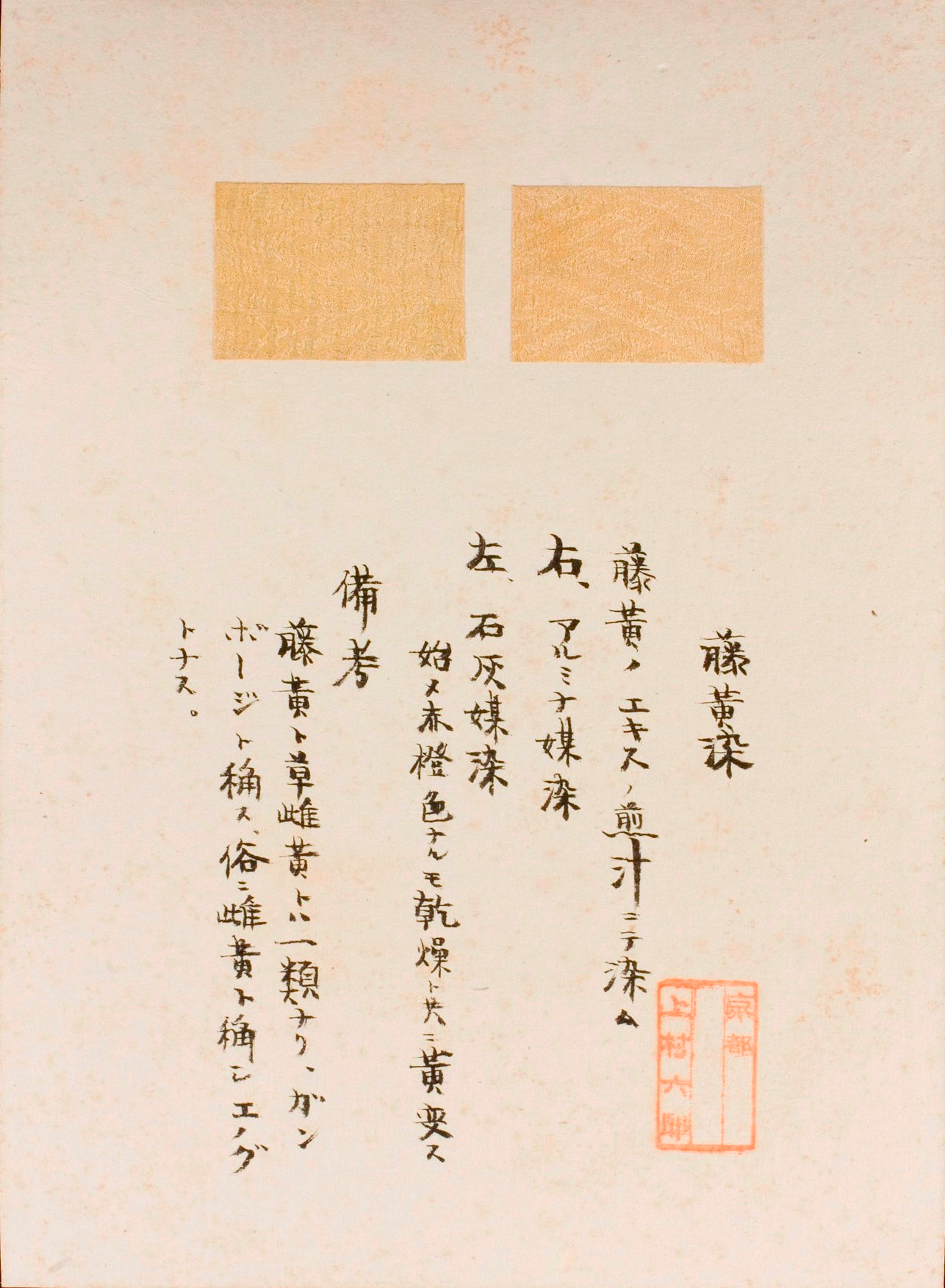

I have read in a couple of places that gamboge was used for dying Buddhist robes. I couldn´t find more information, so I am not sure this is accurate. However, I have discovered an amazing archive of natural dye samples created by the Japanese scholar Uemura Rokuro (1894-1991). The archive has 744 dyed samples of fabric that were obtained in 2008 by the Museum of Fine Arts of Boston (lucky bastards, but also—why did the owners sell such a gem?!).

In the archive, there is a piece of fabric dyed with gamboge (in the picture above). The color is a light yellow, very different from Buddhist robes, but Rokuro made a side note saying the original color right after dying was a red orange, that later changed into yellow.

These color changes are typical of natural dyes and inks. It makes me think that maybe the theory that it was a dye for Buddhist robes could be true. Maybe they knew to use some other ingredient or mordant that made this orange shade permanent? It might be possible.

As much as an interesting pigment as it is, gamboge has some serious disadvantages, the first one being that is very poisonous for humans (a high number of colorants are toxic). The other problem is that it fades when exposed to sunlight.

Therefore, it fails in the two most important categories for colorants: 1. Is it safe? and 2. Will the color stay over time? In both cases, the answer is no. However, and this is fascinating, it seems that the color returns when placed in the dark. Color chemistry really is like magic sometimes.

Despite the downsides, gamboge was collected and used for centuries. It was regularly imported to Europe from the 17th century onwards, maybe earlier. It could be mixed with indigo or Prussian blue to make green, and with burnt sienna to make orange.

It doesn´t mix well with lime, so it was useless in frescoes, and it reacted poorly to lead white. As a result, it would be unsuitable for oil painting, because lead white could not be replaced, while you could find some other yellow that wasn´t gamboge—hopefully a less toxic one.

You can still buy gamboge. Kremer sells the original stuff as a powder, recommending its use as violin varnish. Some other brands, like Rembrandt and Van Gogh, sell gamboge watercolor, although it is not the original pigment, but a modern recreation that is harmless and with a much better lightfastness.

All right, that is all for today! I was planning to talk about other yellow pigments, but this post was turning way too long, so I´ve decided to split it in two parts. Stay tuned for my next post to learn about other fascinating colorants of South Asia.

Chari, C.S., Eremin, K., Jain, A. et al. Characterization of Indian pigments: investigating the color palette of a traditional Jaipuri workshop. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 193 (2025).

Pastoreau, Michel. Yellow: The history of a color. Slovenia: Princeton University Press, 2019.

R. Ploeger, A. Shugar, G.D. Smith, V.J. Chen. Late 19th century accounts of Indian yellow: The analysis of samples from the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Dyes and Pigments, Volume 160 (2019) Pages 418-431.